IT’S ALIVE!

Amplified, naturally

An electric guitar is a living being. It behaves differently when taken into different spaces, when held by different people, or when moved into different climates. It’s alive.

The electric guitar pickup can, in some ways, be compared to a vocal microphone. No matter how expensive and state-of-the-art the microphone you put in front of me is, I won’t sound like Frank Sinatra, unfortunately. I will sound like me. The microphone can sculpt my voice by filtering or boosting frequencies, but the purpose of it is not to render my voice unrecognisable. The purpose of a microphone is to listen to and pick up my voice, so that it can be amplified in the most favourable way.

Sculpting the voice of your guitar

I view the magnetic pickup of an electric guitar in much the same way. A common claim is that the magnetic pickup captures only the vibration of the strings—not the sound of the guitar. At first glance, that seems true.

However, the way the strings sound—the way their harmonics are enhanced or canceled—is heavily influenced by the object they’re attached to. In other words, the guitar itself plays a significant role. And the more sensitive and transparent the pickup, the more the character of the entire instrument comes through.

Too muddy waters?

A typical scenario is that a guitar sounds dark and muddy. The player wants to improve it by changing the pickups.

To some extent, this may work—but only if the reason for the muddiness traces back to the original pickups. Often, however, it is the acoustic properties of the guitar dictating what the amplified sound is like.

No matter what pickups you put into an acoustically dark-sounding electric guitar, the muddiness will come through in the amplified tone.

You can fine-tune the sound and alter the way the guitar drives your amp by changing pickups, but the foundation—the guitar itself—needs to be right. The acoustic sound of your guitar needs to be healthy.

Does changing pickups always help?

Another example: a great-sounding electric guitar typically needs to have a good dose of certain mid frequencies and sparkling highs to cut through in the mix. If your guitar doesn’t provide those frequencies acoustically, you’re out of luck. Changing pickups won’t help—if the frequencies aren’t there, they’re just not there. A pickup can’t put back something that doesn’t exist.

The acoustic feedback

To add more elements to an already complex phenomenon, we also have to deal with acoustic feedback. By this term, I mean the sound waves created by the space (room, hall, or whatever) in which we’re playing the guitar. The louder the amp, the more it will feed back into the parts of the guitar and the strings, making them vibrate differently—cancelling or coupling frequencies—further sculpting the sound. I describe this phenomenon in more detail in another article called Tone Talk.

I sound different from you

And let’s not forget the player! The same guitar can sound completely different in someone else’s hands than in yours.

Stand out from the crowd

I often describe great tone with attributes like transparent, dynamic, or healthy. When the acoustic sound of an electric guitar is healthy to start with, it’s a rewarding situation to choose pickups for that guitar. Why? Because now the function of the pickup is not to do all the work but to amplify the healthy sound of the guitar in the most natural way. If desired, we might want to tweak a bit of this and that with the characteristics of the pickup.

In an extreme musical genre, such as metal, the tone of the guitar is typically processed to a dramatic extent. In this case, we might want to push the envelope further with the choice of pickups. Still, no matter the music style, it’s so much easier to make the amplified sound stand out from the crowd in an exceptional way when the guitar itself sounds healthy to begin with.

WORKING WITH HARRY HÄUSSEL

Precision engineering from Germany

I realized very early in my career that I couldn’t do everything by myself. I just didn’t have the time. And I’m not really a solo act at heart and soul—I enjoy working in a team much more.

One of the first people I ever teamed up with was Harry Häussel from southern Germany. I got to know Harry toward the end of the 1990s when we met at the Frankfurt Musikmesse. I had some ideas regarding pickups for my guitars, and from the beginning, I felt we were very much on the same wavelength.

My first own pickup design comes alive

Our first project together was the design of my first own pickup. I had worked out some parameters for these humbuckers with Finnish guitarist Peter Lerche. Harry made me prototypes with different magnets and coils until we settled on what was then named the Dukebucker.

Dukebucker

The Dukebucker is a low-output pickup. Especially the neck unit is unique, with significantly less winding than traditional neck humbuckers. Our idea was to make these pickups clear and wide-spectrum. So even if they’re in the same ballpark as classic PAF-style pickups output-wise, they have a distinct character of their own that works beautifully with my guitars.

Do you need more oomph..?

We also use many of Häussel’s standard pickups—such as the Broad or BigMag for our Mojo, or the Tozz for the Hellcat—but over the years, we’ve come up with quite a few tweaks of our own. Harry has shown never-ending forbearance, continuing to work with me and push the envelope further.

Typically, our phone calls regarding a new pickup go something like this: I explain in a very obscure way, “This guy wants more ‘oomph’ to his bridge pickup—can you do that?” Harry patiently asks me a few more questions to understand what the hell I’m talking about. Sometimes, he might simply respond, “Yeah, I think so—I’ll send you something to try out.” And most of the time, he nails it on the spot!

Singlecoil dynamics

Another example of our own pickups is the SingleSonic, which we launched in 2001. I’ve always loved P90 pickups, so I asked Harry if we could make something that looks like the Dukebucker but has the characteristic P90 sound. The pickup is almost like a P90—but not quite, since the magnets are a different size. Nowadays, we use the SingleSonic in many different guitars.

In VSOPs, it’s often used in calibrated sets of three, whereas in a Mojo, the SingleSonic typically sits in the neck position. This pickup is one of my all-time favorites—it mixes extremely well with the Dukebuckers.

Sound matters

I refuse to “buy” preconceived opinions on how to get the best sound. Even though hearing sound is a subjective and emotional experience, I approach sound matters with the same pragmatic angle I use in making the actual guitar. I carefully study what already exists, I experiment, and I eventually form my own conclusions based on a vast array of criteria. Some examples follow.

Staggered polepieces or not?

We have single-coil pickups called the VS Classic and VS Blues. They’re not too far from Harry’s own ST Classic and Blues—which are really great pickups as they are. We just wanted a couple of tweaks, such as radiused polepieces rather than staggered ones. We also preferred screened cables over the cloth-covered vintage type.

It’s the little tweaks

We wanted these small changes because I’m not into “tradition for the sake of tradition” thinking. Take the staggered polepieces, for example—they made perfect sense back in the 1950s when the only available strings were heavy gauge with a wound G string. The materials used in strings were different, too.

Staggered polepieces were introduced to compensate for the uneven response of those old-timer strings. Today, with better-made and more balanced strings, radiused polepieces make more sense to me. But hey, no reason to be offended—there’s certainly no right or wrong in these matters. If you feel that staggered poles are the secret to the greatest tone, then that’s the way for you to go.

Gimme Steam

There’s one rather unusual story related to our pickup developments elsewhere on this website. The spotlight article I’m referring to is called Gimme Steam, and it tells how the pickups for our Steam bass were born.

Unraveling and becoming

Looking back, moving forward

I wrote the above article fifteen years ago. Now I’ve sat down to write an additional chapter in the aftermath of our recent release (February 2025) of the first-ever pickups wound here in Harviala, Finland.

I was curious to read through my old article, which I hadn’t so much as glanced at for years — maybe what I thought then doesn’t match what I’m thinking now? What if I felt the need to revise the past to better fit our imagined future?

My predicament now, after having squeezed myself into the rabbit hole of learning to wind pickups throughout 2024, was this: All these years, I’ve told people that we choose not to make our own pickups. So… what’s up with the change of mind?

It’s the Valvebucker’s fault!

The truth is, we dove deep into that rabbit hole already a long time ago. The long, winding, and sometimes frustrating road of designing the Valvebucker slowly but surely shifted my mindset about making pickups. While the Valvebucker remains something of an anomaly — serving a super niche group of players — what my team and I learned on the rollercoaster ride of bringing it to life was this: even when everyone says it’s impossible—or if possible, that it wouldn’t make sense—there’s a chance they’re wrong—and you’re right.

Letting go of certainties isn’t easy — but it is necessary if you want to create something new. Encouraged by the success of the Valvebucker, we realized we might have something relevant to say in the world of electric guitar pickups for a much wider audience, too.

The realm of tone

Looking back, transparency in tone was something I was already seeking thirty years ago. Reading through my old article, I was struck by how much of how I see things today was already there. I was working with Harry Häussel even before Jyrki, Tomi, or Emma joined my team—striving toward the same goal I’m still pursuing.

The fundamentals of how I approach pickup design—the way great guitar tone emerges from the interplay between the instrument, strings, pickups, and player, further shaped by the rest of the signal chain and the room you’re in—form a complex equation. And this—the continuous urge to explore the different facets of the realm of tone—remains an endless source of amazement and inspiration for me. It is the connecting agent between you and me.

The PAF mirage

The late 1950s to early 1960s PAF pickup, developed by Seth Lover for Gibson guitars, is one of the most sought-after electric guitar pickups in the world. Saturated with myths, it has probably been studied and reverse-engineered more than any other pickup. Some makers have dedicated their entire careers to unraveling the secrets of the PAF—yet certain parameters behind those wonderfully open and articulate-sounding humbuckers remain a mystery.

Why? Because the “human factor” of the build process back then makes it impossible to know every detail. Plus, each pickup was slightly different from the next, adding to the intrigue and elusive nature of the original PAFs.

Wood vs. copper wire

Those who have followed my work know that reverse engineering the past has never been my thing. I’m interested in getting the sound and the feel right – but I don’t lose sleep over whether something is authentic in the strictest historical sense.

I also believe that if I focused on mechanically replicating the exact historical form of a pickup, I’d be looking in the wrong direction—shifting my attention away from the big picture (the sound and feel) and getting lost in the nitty-gritty details. And that’s just not what interests me.

I mean no disrespect—it’s just not what drives me. If it were, I’d never have tried making an electric guitar out of Spanish cedar. I wouldn’t have swapped flamed maple for figured birch. I wouldn’t have experimented with thermally aged wood back in the 1990s—at a time when nobody outside of Finland had heard of it.

With guitars, we work with materials that are never the same. To achieve consistently outstanding results, we adapt the building process to the natural variations in wood. This adaptability—one luthier making one instrument from start to finish, without serial production or automation—is a key reason our guitars and basses are so highly praised by our customers.

Pickups, however, are a different story. A magnetic pickup is more a product of precise engineering than organic craftsmanship. While materials like magnets and wire may vary slightly over time, the challenges a pickup maker faces are essentially quite different from those of a guitar maker.

Measuring the immeasurable

The hand-wound data bank?

If I spent a decade (or two) hand-winding pickups, I’d probably get pretty good at it. But even if I did—how would I pass that knowledge on to someone else? If I stumbled upon a fantastic pickup “recipe,” how would I record the data? I could note the wire gauge, insulation type, number of turns, the DC resistance and certain subjective observations of the winding process—but some of the most critical factors that define the pickup’s sound are harder to capture. The tension of the wire, the pattern in which those thousands of turns are layered onto the bobbin—this is all crucial hard data, yet nearly impossible to quantify and repeat when hand-wound.

The Catch-22

Imagine this: You’re hand-winding a pickup, holding that ultra-thin copper wire between your fingers as you guide it onto a spinning bobbin. The counter clicks with each turn. When you’re done, you assemble the pickup, install it in a guitar, and listen. If it sounds good—great! If not, you start over: bobbin spins, wire steers, you listen again. Repeat that cycle for years, and—if you’re paying attention—you’ll improve. You begin to notice things like, “Ah, holding the wire a bit tighter changes this…” or “Steering it that way sounds better…”

There are masters of pickup making who have honed their craft and artistry through that grind. And yet, my ultimate Catch-22 remains: even after winding thousands of pickups by hand, you still wouldn’t fully know the exact parameters—the complete recipe—behind each one.

The hidden guesswork

Hand-winding inherently involves a level of guesswork—and honestly, that’s something I’d rather avoid. I’m not drawn to filling gaps in data with the mystique of “hand-wound.” Without reliable, measurable parameters, achieving consistency is nearly impossible—and refining your process over time becomes that much harder.

Maybe it’s partly due to Harry Häussel’s long-term influence—his delightfully precise dose of fine German engineering has clearly rubbed off on me!

I need to know, inside out

The way I see it, the only way to understand the pickup for real is to grind my way through and learn to know what every parameter does. I want to increase or decrease the wire tension by a single gram and see how it affects the sound—or adjust the tension gradually across the coil and see what it does. I want full control over how many turns I wind per layer, how different scatter-wound patterns sound, and—when it’s right—I want to be able to repeat it.

I need to know everything there is to know and have complete control, so you can trust you’ll get a 100% result from us every time.

And, as counterintuitive and uncomfortable as it may sound—coming from someone who has dedicated his career to the artistry of guitar making—a significant part of that level of knowledge simply isn’t accessible through hand-winding.

In other words, here’s what I’m suggesting:

The hand-wound PAF pickup from the 1950s set the bar incredibly high. Those humbuckers aren’t called the Holy Grail for nothing.

And yet, in today’s world, I firmly believe that hand-winding is not the key to reaching that bar.

Why? Because:

1. Modern technology can replicate any winding pattern—simulating even the most intricate hand-wound processes with extreme accuracy.

2. Hand-wound trial and error will always lose to modern trial and error, because with hand-winding, some of the most crucial parameters can’t be recorded or repeated.

Breaking the myths of pickup making

Not in my lifetime!

If someone had told me ten years ago that we’d one day be winding pickups using state-of-the-art, fully automated machinery… I would’ve laughed. Not in my lifetime, I would’ve said.

And I would’ve been wrong.

That is exactly what we’re doing now. Technology has taken enormous leaps, allowing a small builder like us to gain a deeper understanding and precise control over what happens inside a magnetic pickup. We can fully control every parameter, scatter-wind any pattern we like, and—crucially—repeat the process with absolute accuracy.

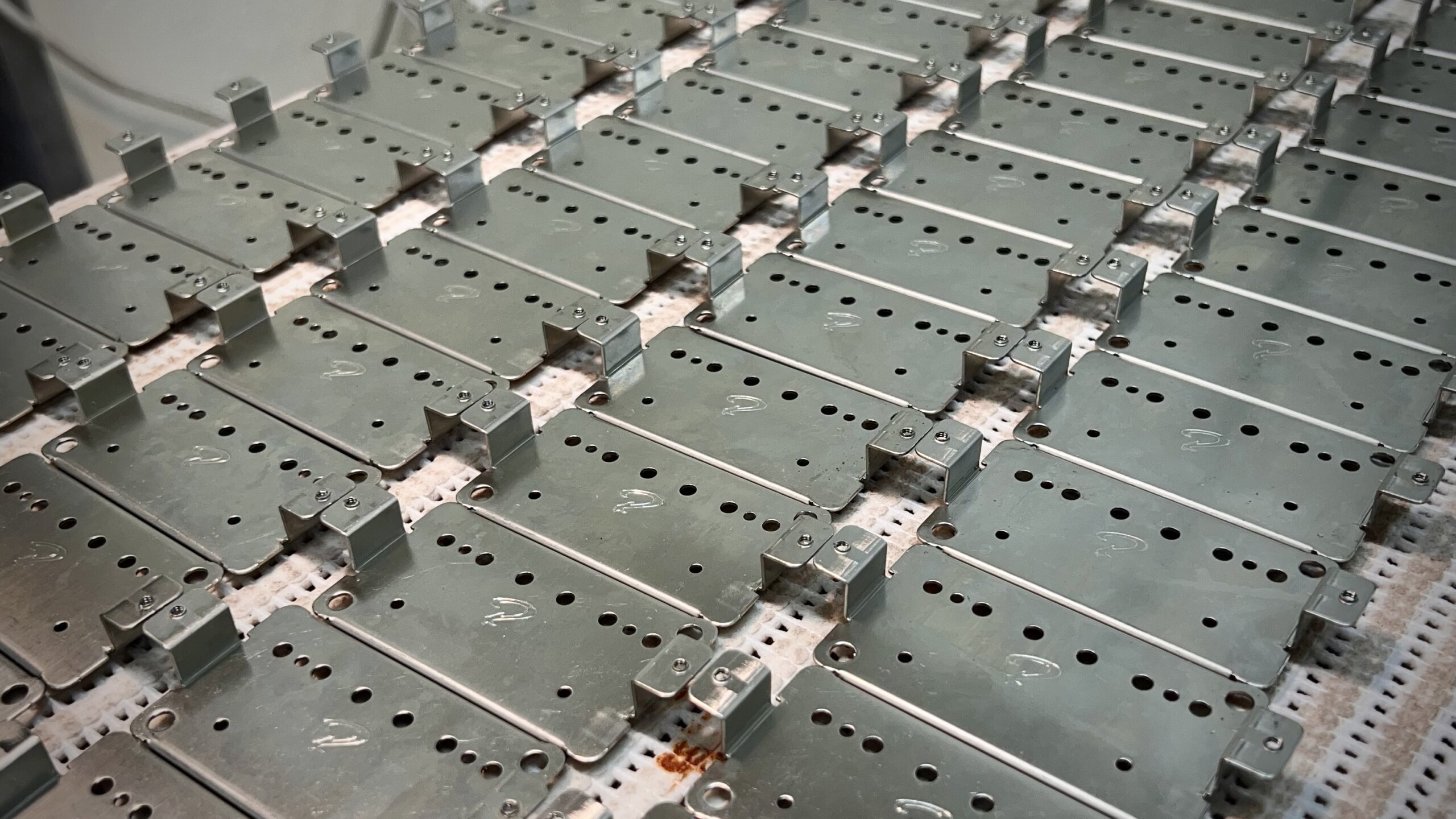

A quick disclaimer, though. While our winding process is fully automated, it is not outsourced. Every step happens right here in our workshop in Harviala, under our own hands and eyes. And beyond the winding, the rest of the pickup-making process still follows our time-honored, traditional routines.

The Power of Precision

This means we can improve our pickups through a true trial-and-error method: change one parameter, test, adjust one variable, test again—continuing that cycle endlessly while carefully documenting every step forward or backward.

It might sound exhausting, but in reality, it’s incredibly satisfying and exciting. In just about a year, we’ve learned more than we ever imagined about what really shapes the sound of a pickup.

What we thought we knew

We’ve always known—or at least assumed—a lot about pickups. Things like: Alnico 5 magnets are stronger than Alnico 2. A brass baseplate softens the sound compared to nickel silver. And a million other details. Just like in guitars, every element seems to matter.

But there’s a distinct difference between hearsay and hands-on experimentation. Are these things really as others say? Or could some long-held beliefs be based on assumptions rather than hard data—misconceptions shaped by inadequate measuring tools? Maybe even myths waiting to be debunked?

The past year has taught us that a handful of key parameters shape about 95% of a pickup’s sound—while many other factors contribute in smaller ways.

Separating what matters

The coils are, without a doubt, the most crucial element. There’s no question about it. Copper wire quality and gauge, insulation type and thickness, the number of turns, coil dimensions, turns per layer, and wire tension—these factors define most of a pickup’s character.

Next in line is the magnet and the components it magnetizes—the pole pieces, screws, and surrounding parts. Interestingly, adding a nickel silver cover to a humbucker seems to impact the sound as much as the magnet type does.

Then there are details like the baseplate, bobbin material, screws, and other small components—elements that may or may not influence the sound.

A healthy way to separate what matters?

• If I can hear a difference, it means something.

• If I can measure (DC resistance, impedance, inductance, capacitance, Q-factor, frequency response) a difference but not hear it, I turn to my trusted network—people whose ears I trust more than my own.

• If I can neither measure nor hear a difference, it’s probably not important.

The Missing Data

The biggest realization for us, however, has been this: The numerical data that pickup manufacturers—big and small—typically disclose boils down to DC resistance, magnet type, and wire gauge. And that’s about it.

What nobody discloses? Wire tension, turns per layer, or any specifics of the winding pattern. In other words, the most crucial factors shaping the sound remain a mystery. Not only because this data is the hardest (if not impossible, to some extent) to reverse engineer—but also because the pickup maker who hand-winds his coils, doesn’t have all the numeric data, regardless of how skilled or how great his pickups may be.

And that’s no coincidence.

This information isn’t just trade secrets—it’s the crucial intangible property of pickup making. Or, put another way, it’s what fuels the myths that surround it.

Finding our own voice

The Formula

In late 2023, we set our first goal: to create a humbucker set that we loved. Yes, rooted in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s PAF territory in terms of response, sound, and feel—but I wasn’t interested in just copying what had been done before. No cloning, no following the beaten path. The world doesn’t need another set of PAF replicas. There are already enough of those.

A brutal reality check

We wound our first set using all the classic ingredients—Alnico 5 magnets, plain enamel wire, the works. We programmed our machines, hit start, and when we got it assembled… the pickups sounded like crap. Really disappointing.

Okay, we knew we wouldn’t get it perfect on the first try—but that bad? That’s when it hit us: Making great pickups isn’t easy. If it were, every pickup in the world would sound great.

The six-month grind

For over six months, we chipped away at the learning curve—one small change at a time. Trial and error. Wire type, magnets, winding patterns—everything. But more than anything, we learned how much the coil matters. Tiny differences in wire tension and winding pattern made massive audible differences.

We figured out how to brighten the sound, darken it, add bite to the attack—or even too much bite. Eventually, we landed on a set of humbuckers that made us stop and say: “This is actually pretty damn good!”

Tone Tasting

At this point, we decided to put our ears to the test with a little tone tasting event at Antti Paranko’s studio. Another great guitarist, Marko Karhu, joined us. I also picked up my friend Löffe—and his original ‘59 Burst Les Paul, which is probably worth more than our entire workshop building.

Antti had a bunch of his guitars, Marko brought his limited edition Custom Shop Les Paul, I had my trusted Unicorn #1 and Tomi had his similar one, both equipped with our new, still-unnamed pickups.

What followed wasn’t a scientific test—just pure feel, sound, and vibe. And here’s what we found:

• That original ‘59 Burst Les Paul? The PAFs in it were breathtaking. They had a freshness to them—almost like single coils, yet not. No matter how hard you hit the strings, they never sounded harsh or spiky. At the same time, they were dynamic and effortlessly expressive.

• Marko put it best: “The notes and chords just flow out of the guitar. It sounds right every time.”

Our new pickups in comparison?Compared to the ‘59, our new pickups had similarities—but they also felt… restless. They sounded great, but they weren’t as effortless to play.

Emma described it best: “Our pickups sound younger—not as matured or relaxed as the ‘59.”

The conclusion? Our new pickups were really good—but not quite like the old PAFs.

The final tweaks

That day left my head buzzing with ideas. Over the following weeks, Jyrki, Tomi, Emma, and I had long discussions about what we had heard—what worked, what didn’t, and most importantly, how to bring some of that relaxed ease into our pickups.

By this point, we had spent months listening to every stage of our pickup’s development, and we had a strong hunch about what needed to change. In just a few more weeks—and about 5 or 6 parameter adjustments—we nailed it.

No, it wouldn’t be identical to a ‘59 PAF—but it didn’t need to be. What we wanted was the feel of having arrived—of capturing the essence of an inspiring humbucker that works beautifully across a wide range of music and playing styles.

Wax on, wax off

A new possibility emerges

By October 2024, we had something special in our hands—a set of pickups that felt like a perfect match for our guitars. And the more we played them, the more we started thinking:

These sound so good… maybe we should sell them separately, too.

But before we could even consider that, there was still one big question left to answer.

The one flaw in vintage PAFs

As much as I love a great PAF, there’s one thing I don’t enjoy about them: their unpredictability when it comes to microphonics.

Back in the day, those wonderfully articulate and lively PAFs were made without wax potting—a process that later became the industry standard to control feedback as volume levels increased. And that’s where most of the industry has stayed.

Today, there are two camps in pickup making:

• Many manufacturers acknowledge that unpotted pickups sound more open, airy, and present—but they avoid making them due to practical issues.

• Some old-school builders stick with unpotted pickups, fully embracing their tonal qualities despite the potential problems.

The Cake Conundrum

But… we wanted to both eat the cake and keep the cake! We wanted the airy sound of an unpotted pickup—but without the microphonic issues that come with it. That’s where things got complicated. Suddenly, there was no one offering that option. At best, the solution was a vague, “Well… we can pot it a little, but it won’t sound quite the same.”

In other words, conventional wisdom said you had to choose one or the other. We thought… maybe not.

Stubborn? No – it’s called Sisu!

I know I’m stubborn. My team is stubborn. But in Finland, we have a word for that: sisu. It’s more than just stubbornness—it’s the relentless drive to push forward, no matter how difficult the challenge.

And this was a challenge we had to solve.

We told ourselves: “There has to be a way to do this differently.”

The first attempt: A failure

So, we started where everyone else does—a traditional paraffin and beeswax mixture, letting the pickups soak until no more air bubbles surfaced.

The result? A huge disappointment. Not a shock, but still frustrating.

The pickup still sounded good… but that air, that presence, that articulation? Gone. What we had now was just another well-made humbucker—nothing more.

So, we kept going.

We experimented with different waxes, lacquers, even superglue (like Alembic did back in the day!). We tried quick dips, preheating the pickup in an oven before a short wax bath.

But no matter what we did, the result was always the same: that special sparkle of our unpotted pickup disappeared.

Calling in the Wizard

At this point, I called my good friend Lassi Ukkonen—the electronics wizard behind our Valvebucker circuit. I unloaded my frustration, walking him through every failed attempt to stabilize the coils without sacrificing the sound.

Lassi patiently explained: It’s inevitable.

When a coil is unpotted, the wires can move ever so slightly. Once you replace the air with wax—or anything else—you not only stop that micro-movement, but you also change the coil’s inductance. Air has a different insulation value than wax, lacquer, or anything else we had tried.

Beam me up, Scotty!

What if…

“So, there’s no way around it? That’s what you’re saying?” I pressed.

Lassi started brainstorming: What if we could control the stabilization process more precisely? What if we could “freeze” certain parts of the coil while leaving other sections untouched?

That might work—but it would require an entirely different approach to winding. We’d have to figure out how to stabilize specific areas of the coil as we wound it, leaving other sections untouched.

Good news and bad news

On one hand, we had a new spark of hope. On the other, we realized we were nowhere near a final product if we pursued this.

Up until now, we had been winding pickups like everyone else—whether by hand or automation. But now? Now we were talking about potentionally reinventing the entire process.

And that was both terrifying and thrilling.

The Secret Remains The Same

Remember when I talked about trade secrets—the intangible property of pickup making?

Well, my dear friends, from this point on, I can’t share every detail with you. I hope you understand.

But I promise—I’ll only leave out the part that a pickup maker would need (sorry!). As a player, you’ll know everything that matters.

A breakthrough!

After another three months of relentless trial and error, we finally cracked the code.

We found a way to control microphonics while preserving every nuance of the pickup’s natural sound—exactly as it was unpotted.

It’s a novel method that allows us to stabilize different sections of the coil with precision. During the winding process, we can choose which coil segments to solidify and which to leave untouched.

The result?

• Zero compromise on sound quality

• Resistant to uncontrollable feedback at high volumes

• A pickup that retains the airiness and articulation of an unpotted coil—without the risk of squeal

100% plant-based

We also found the perfect agent for stabilization—one that’s repairable, sticky and flexible rather than hard and brittle—similar to how an ideal wax mixture behaves.

And, as a side note, unlike the commonly used beeswax, our special agent is 100% plant-based—making our pickups fully vegan-compatible.

We call it Flux-Coil™ Stabilization

I know—it sounds like something straight out of Star Trek—maybe Scotty fine-tuning the warp core or Doc Brown yelling about the flux capacitor!

But this isn’t science fiction—it’s real, and it’s all about controlling the unseen forces that shape your guitar’s sound.

In turntable cartridges, moving magnet and moving coil designs interact with magnetic fields in different ways. Similarly, the winding and stabilization process of a pickup affects how the coil interacts with the magnetism at its core.

Flux refers to magnetic flux, the invisible yet fundamental force that drives how a pickup responds to string vibrations. In our method, we stabilize specific coil segments while leaving others free, carefully managing how the coil interacts with the magnetic field.

Unlike traditional potting—which locks the entire coil in place, alters its properties, or at best, can’t be precisely controlled—our approach preserves the natural movement of the coil where it matters most. The result? A lively, dynamic, transparent tone—just like an unpotted pickup—without the risk of uncontrollable feedback.

This is what makes Flux-Coil Stabilization unique: it protects the integrity of the tone while ensuring stability at high volumes.

The firstborn: Väinö & Aino

May I proudly present to you:

The firstborn set of humbuckers made in Harviala, Finland, at the Ruokangas Guitars workshop.

Meet Väinö & Aino

We call the bridge pickup Väinö and the neck pickup Aino—both traditional Finnish names, Väinö typically for a boy and Aino for a girl. You can find more details about them on the Ruokangas Artisan Pickups page. And this is just the beginning—we hope to bring you many more pickup models for both guitars and basses in the future. The game is on!

Available Now

I’m happy to share that we decided to make Väinö & Aino available for aftermarket use—not just in our guitars. You’ll find them in the Ruokangas Shop, customizable with:

• No covers for that familiar open look

• Traditional covers for a classic touch

• Ruokangas custom covers for something truly special

Still a team effort

Our collaboration with Harry Häussel, and occasionally other incredible pickup makers, will continue as always. We have no illusions of becoming fully independent in pickup-making anytime soon—but this journey has opened new doors, and we’re excited to explore where it leads.

In the meantime, remember:

Happiness is playing the guitar you love… as loud as you want! 🎸🔥